Do Meta-Analyses Oversell the Longer-Term Effects of Programs? (Part 1)

Detecting Follow-Up Selection Bias in Studies of Postsecondary Education Programs

The U.S. Department of Education’s What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) recently published a practice guide for educators on Effective Advising for Postsecondary Students. One recommended practice is to “transform advising to focus on the development of sustained, personalized relationships with individual students throughout their college career.” The evidence in support of this practice includes a meta-analysis showing that five programs using this approach increased postsecondary graduation rates by 0.29 standard deviations—around 13 percentage points—on average.[1]

We think this is probably an overestimate of the true effect of this practice on graduation rates. The five studies that collected data on graduation came from a pool of nine studies that estimated effects on academic progress, a shorter-term outcome than graduation. These five studies with graduation data had much larger effects on academic progress than the studies that did not estimate effects on graduation. To demonstrate the issue, this post shows the problem using a meta-analysis of studies conducted by MDRC before showing results for the WWC example.

Why Studies with Long-Term Follow-Up Might Be a Biased Group

The problem discussed in this post has been recognized for a while. For example, Watts, Bailey, and Chen discuss several reasons that studies with larger shorter-term effects might be more likely to collect longer-term follow-up data than those with smaller shorter-term effects.[2] One reason is that a small short-term effect might encourage someone to strengthen an intervention’s design rather than collecting longer-term follow-up data. Likewise, funders may prefer to allocate their resources to interventions with a higher likelihood of producing positive longer-term effects. Finally, authors or journal editors may decide not to publish studies with small short-term effects that also have small longer-term effects. Whatever the reason, Watts, Bailey, and Chen note that selecting studies for longer-term follow-up data collection based on short-term effects may provide an overly optimistic picture of the longer-term efficacy of a class of interventions.

We refer to this phenomenon—where longer-term follow-up data are available for a selected sample of studies among all studies of a class of interventions—as follow-up selection bias. We expect it will typically lead meta-analyses to overestimate longer-term effects for the range of interventions under consideration.

An Example with Some Great Data

We first present results from a meta-analytic data set of 30 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of 39 postsecondary interventions, including over 65,000 students.[3] This data set, known as The Higher Education Randomized Controlled Trials or THE-RCT, is available to researchers through the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR). All 30 RCTs were conducted by MDRC.

These RCTs range in size from about 900 students to 10,000 students and from 1 to 10 community college campuses. They tested diverse interventions ranging from low-intensity approaches such as informational messages that encouraged summer enrollment to comprehensive interventions such as the City University of New York’s Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP), which included support services (enhanced advising, tutoring, and career services), three forms of financial support (a tuition waiver, transportation passes, and free textbooks), and more. Although all studies followed students for one or two semesters, studies of only 12 of the 39 interventions include full-sample information on whether students graduated within six semesters. The average effect of these 12 interventions on graduation by the sixth semester after random assignment is 4.6 percentage points.

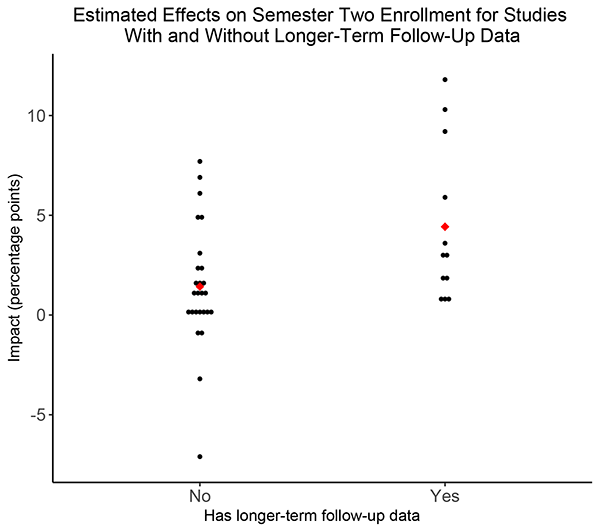

Figure 1 shows the distribution of effects on a short-term outcome for the studies that did not measure graduation for all sample members (labeled “No”) and the 12 that did (labeled “Yes”). The short-term outcome is the percentage of students who were enrolled in their second semester after random assignment. As can be seen, all the “Yes” studies have short-term estimated effects that are positive. In contrast, many of the “No” studies have short-term estimated effects that are null or negative. The weighted average estimated effect on second-semester enrollment is 4.4 percentage points for “Yes” studies but only 1.2 percentage points for “No” studies. This pattern could generate follow-up selection bias in a meta-analysis of longer-term intervention effects.

Figure 1: Short-term estimated effects from the THE-RCT sample

Returning to the What Works Clearinghouse Case

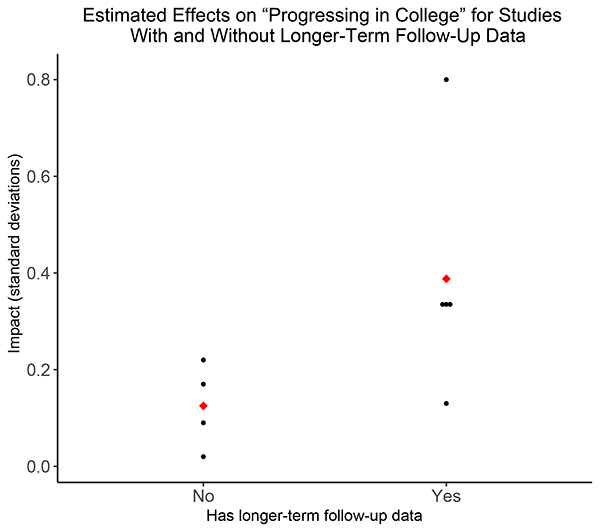

Figure 2 shows estimated effects on a short-run student outcome—progressing in college—for studies that did and did not estimate effects on graduation rates.[4] As was the case with studies from THE-RCT, studies that did measure effects on graduation rates found larger effects on progressing in college than studies that did not. The weighted average effects are 0.44 and 0.14 (in effect size units), respectively. Again, this pattern is likely to result in follow-up selection bias in meta-analytic estimates.

Figure 2: Short-term effects for the WWC sample

Implications

The most obvious implication of this work is to beware of meta-analyses that present results on longer-term outcomes! They might represent a set of studies that had larger short-term effects than a typical study might find and that therefore overstate the effects of this type of intervention on longer-term outcomes. When one performs a meta-analysis on longer-term outcomes, one should also make a comparison like the ones outlined here among studies that meet all other meta-analysis inclusion criteria: comparing effects on shorter-term outcomes in studies that did and did not have longer-term follow-up data. A companion post provides some options for attempting to correct for follow-up selection bias in a meta-analysis.

[1]The practice guide does not provide the estimated effect on graduation rates in percentage points, but the effect would be 13 percentage points if 25 percent of the control group graduated, a common three-year graduation rate at community colleges.

[2]Tyler W. Watts, Drew H. Bailey, and Chen Li, “Aiming Further: Addressing the Need for High-Quality Longitudinal Research in Education,” Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness 12, 4 (2019): 648–658.

[3]John Diamond, Michael J. Weiss, Colin Hill, Austin Slaughter, and Stanley Dai, “MDRC’s The Higher Education Randomized Controlled Trials Restricted Access File (THE-RCT RAF), United States, 2003-2019,” Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR37932.v2.

[4]For WWC’s definition of “progressing in college,” see page 8 of the WWC Review Protocol for the Practice Guide on Effective Advising for Postsecondary Students.