Effectiveness of Pretrial Special Conditions

Findings from the Pretrial Justice Collaborative

Background

As more jurisdictions across the country are seeking to reduce their jail populations, many view electronic monitoring (the use of an electronic device to monitor a person’s movement and location) and sobriety monitoring (regular drug and alcohol testing) as potential alternatives to pretrial detention that can offer peace of mind to decision-makers and the public. In theory, the added layer of supervision that special conditions provide should encourage people to appear for court dates and avoid activities that could lead to new arrests. Yet most studies of the effectiveness of special conditions have faced methodological limitations and have yielded mixed findings.[1] Furthermore, special conditions such as electronic monitoring and sobriety monitoring carry significant costs—both personal and monetary—for those being monitored and for jurisdictions.[2]

Methods

To examine the effectiveness of electronic monitoring and sobriety monitoring in encouraging court appearance and the avoidance of new arrests, the MDRC research team conducted impact analyses using a nonexperimental propensity score matching design to assess both electronic monitoring and sobriety monitoring.[3] This method allowed the team to compare court appearance and pretrial rearrest outcomes for individuals released with special conditions with those of statistically comparable individuals who were released without special conditions.[4] The team used data on court cases initiated between January 2017 and June 2019 in four U.S. jurisdictions: one small and rural, one medium-sized, and two large and urban. The analysis was pooled across all jurisdictions for which sufficient data were available for a given analysis.

Findings

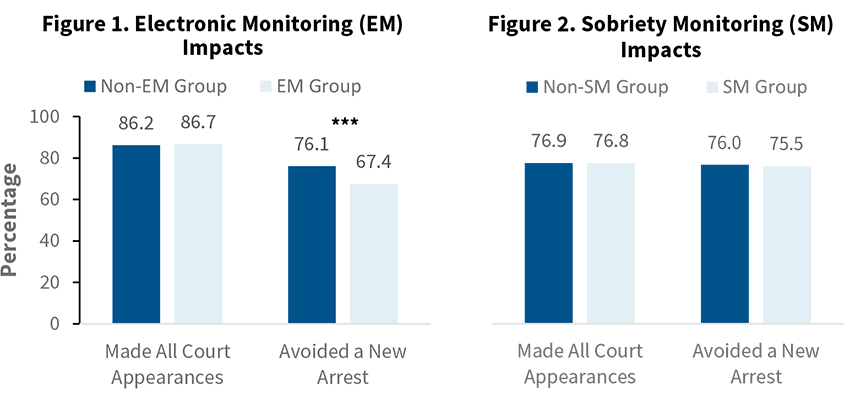

SOURCES: Court and pretrial services data from participating sites.

NOTE: The three asterisks (***) above indicate statistical significance at p < 0.001.

Figures 1 and 2 summarize results from the analyses. Major findings are:

- Being released on electronic monitoring or sobriety monitoring did not significantly improve court appearance rates. As the figures show, the analyses found that the special conditions and non–special conditions groups had similar pretrial court appearance rates. These results were consistent across jurisdictions (not shown).[5]

- Being released on electronic monitoring did not significantly increase the percentage of people who avoided a new arrest during the pretrial period. In fact, the analysis found that the electronic monitoring group had a pretrial rearrest rate about 9 percentage points higher than that of the non–electronic monitoring group, a result that was consistent across the two jurisdictions in that analysis. While the factors causing the results are not definitively known, the difference may be a supervision effect caused by the special conditions groups’ more intensive monitoring. In other words, people may be more likely to be arrested if their actions are more closely monitored, when compared with others who are less closely monitored. Alternatively, the result may reflect unmeasured differences between the special conditions and non–special conditions groups that could not be controlled for in the analysis.

- Being released on sobriety monitoring did not significantly improve the percentage of people who avoided a new arrest, but there was variation in this effect among jurisdictions. In two of the four jurisdictions studied, people who were assigned to sobriety monitoring were more likely to avoid new arrests, while in the other two, the result was the opposite.

Policy Implications

The findings presented here suggest, at minimum, that pretrial release with electronic monitoring is no more effective than pretrial release without electronic monitoring in promoting compliance with the universal pretrial release conditions of making all court appearances and avoiding new arrests in the pretrial period. The results also suggest that people assigned to electronic monitoring may have higher pretrial rearrest rates. Although the reasons for this effect are beyond the scope of this analysis, the finding certainly suggests that additional cross-site studies of electronic monitoring at the pretrial stage are needed. As with electronic monitoring, sobriety monitoring also appears to have little effect on court appearance rates, but its relationship with rearrest appears to be more complicated. Overall, these findings warrant cautious reflection among policymakers and practitioners on the use of special conditions, particularly considering their high personal and financial costs to affected people and jurisdictions.

[1] Jyoti Belur, Amy Thornton, Lisa Tompson, Matthew Manning, Aiden Sidebottom, and Kate Bowers, “A Systematic Review of the Electronic Monitoring of Offenders,” Journal of Criminal Justice 68 (2020): 101686; Ross Hatton, Research on the Effectiveness of Pretrial Support and Supervision Services: A Guide for Pretrial Services Programs (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina School of Government Criminal Justice Innovation Lab, 2020).

[2] Chaz Arnett, “From Decarceration to E-carceration,” Cardozo Law Review 41, 2 (2019): 641; Sarah Cornett, “The Fraught and Expensive Cycle of Drug Testing” (website: https://www.arnoldventures.org/stories/the-fraught-and-expensive-cycle-of-drug-testing, 2022); George Washington University Law School, Electronic Prisons: The Operation of Ankle Monitoring in the Criminal Legal System (Washington, DC: George Washington University Law School, 2021).

[3] One-to-one matching without replacement was performed separately by jurisdiction and by special condition before the samples were pooled for each of the two analyses. Matching diagnostics suggest that the propensity score matching method yielded statistically similar matched comparison groups, although it is possible that the groups differed with respect to unmeasured characteristics.

[4] Sensitivity analyses that included variations in the matching model, replacement, different caliper sizes, and equal weighting of jurisdictions produced similar findings.

[5] The research team also used a regression discontinuity design to assess the effects of electronic monitoring on court appearance and avoidance of arrest. Results were generally in line with what is presented in this brief from the propensity score matching analysis and will be available in full in a technical paper to be published later in 2023.