Employment and Training Services Go Digital

Expanding Access and Reducing Barriers for Job Seekers

Over the past decade, employers across the country have gradually shifted from in-person to virtual hiring strategies for recruitment, job applications, and interviewing. While this shift has been happening faster in some industries than in others, the COVID-19 pandemic hastened the change, particularly in sectors that previously had been slow to adopt virtual techniques, such as retail and food service. Employers anticipated that these pandemic-era hiring strategies would continue long after the pandemic started to slow. Workforce programs that provide employment and training services to help people find jobs responded in kind, adapting existing services to reflect the increasingly digital hiring landscape.

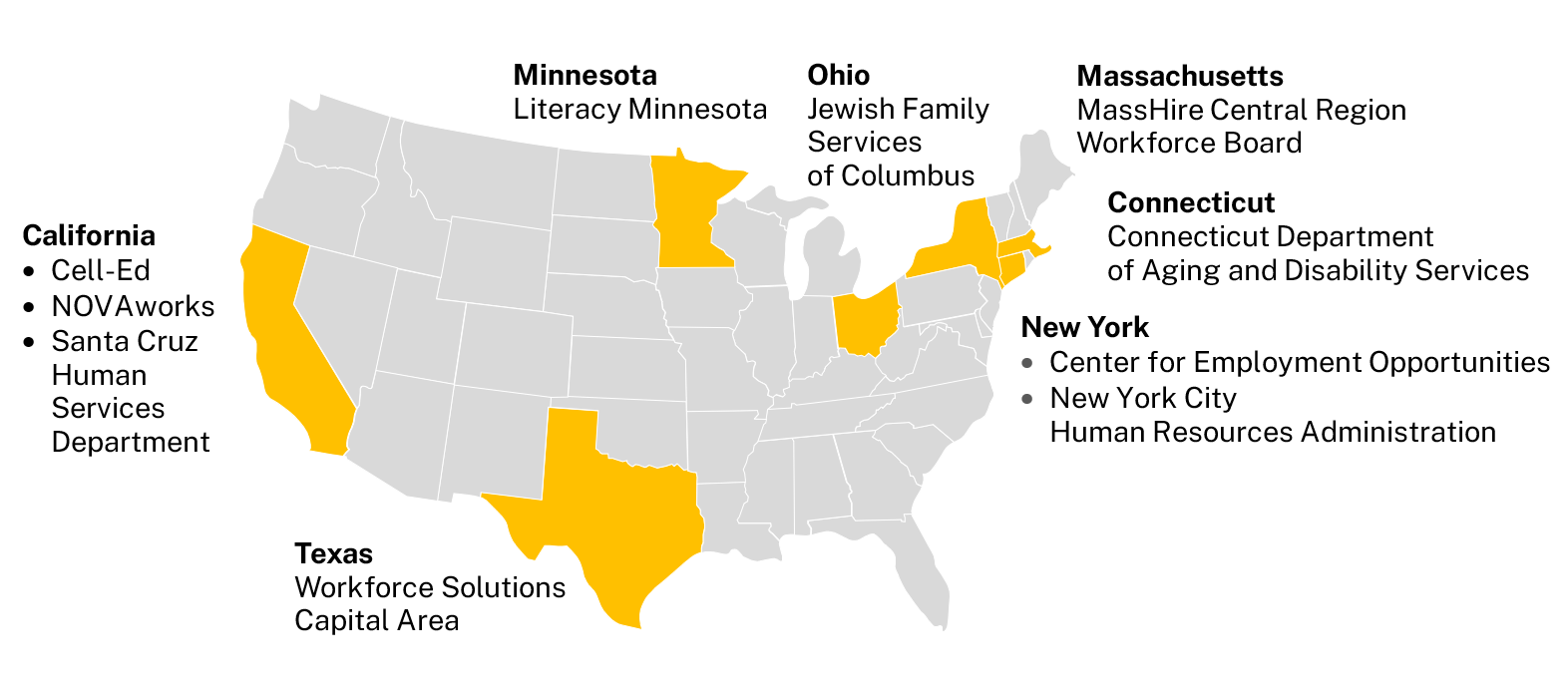

As part of the Building Evidence on Employment Strategies (BEES) project, researchers from MDRC and MEF Associates conducted virtual interviews from November 2021–April 2022 with staff members at 10 such workforce programs to learn how they were using technology to adapt their services during the pandemic. Most of the organizations used a hybrid model to blend in-person and virtual service delivery. (See Figure 1 for a map of the programs interviewed.)

Figure 1. Ten BEES Programs Interviewed About Hybrid Service Delivery

This blog post examines five key adaptations the programs made to accommodate the new hiring context.

1. Blending Traditional and Digital Modes of Service Delivery

Program staff members noted that many clients could no longer apply for positions that had previously accepted in-person applications, such as retail, food service, and independent “gig economy” jobs, during the early stages of the pandemic. In response to pandemic-related restrictions, these businesses increasingly used employment websites such as LinkedIn and Indeed to recruit workers. However, some clients with backgrounds in these kinds of positions had limited work experience with computers, resulting in a gap between the skills they had gained in their previous jobs and the skills they now needed to search for and obtain new positions in the same sectors.

To help bridge this skills gap, the workforce programs provided one-on-one assistance with online job searches. This included helping clients learn how to navigate employment websites, identify desired jobs, fill out online applications, write emails to employers to express interest, and send attached files such as resumes. Program staff members also facilitated mock virtual interviews so clients could test out common video conferencing software programs before doing a real interview. During these mock interviews, staff members advised clients on such things as body language and professional demeanor on camera, appropriate video backgrounds, and adequate audio connectivity. These trainings were particularly important among clients who were formerly incarcerated, older, or transitioning between industries and lacked previous exposure to these techniques.

2. Tailoring Services to Clients’ Needs and Comfort with Digital Platforms

Clients who had faced barriers to accessing services in person said they appreciated the flexibility and increased access that the programs’ virtual services offered. This benefit extended to job searches, too. For example, the ability to apply for jobs online and participate in virtual interviews reduced clients’ travel time and expenses. Virtual job search also allowed individuals to apply to a more geographically diverse set of jobs, potentially opening new opportunities they may have otherwise missed.

But such benefits only accrue to individuals who have the digital tools, skills, and broadband access required to participate in the virtual services. Program staff members feared that those who lacked digital literacy would be at a disadvantage in the virtual job marketplace. Specifically, clients who did not have digital tools prior to the pandemic often did not have the skills required to use them. So even as some programs made efforts to provide digital devices to clients, some clients needed help figuring out the basics of how to use them. Some clients with disabilities had to jump additional hurdles. For example, one organization found that clients with more severe disabilities struggled to access online platforms, navigate digital applications, and complete the personality diagnostics and pre-assessments that were increasingly required by employers. Further, videoconferencing platforms varied in terms of the quality of their accessibility features such as closed captioning. Several workforce programs experimented with different platforms to provide job search services that were accessible to their clients and to prepare them for how to use these features during virtual job interviews. Additionally, one site worked to help clients who were recent immigrants or refugees learn about hiring events by sharing information in a variety of languages on WhatsApp, which staff members said was a popular platform among these clients.

3. Supporting Clients’ Access to Digital Tools and Skills

Many programs found that the first step toward supporting clients with limited computer experience was to ensure that program staff members themselves had the expertise needed to do the training and technical assistance work. For example, some programs invested significant time and resources to train staff members in how to deliver job search services remotely. One program trained its staff in how to facilitate workshops and help clients participate in virtual career exploration conversations. Another program conducted one-on-one training with every frontline staff member in how to facilitate its new virtual job search assistance and training process via Zoom. One program created a training video in which staff members with varied experiences and backgrounds role-played virtual career assessment and exploration sessions. This helped staff members who were nervous about facilitating such workshops feel more comfortable.

The second step for many programs was to ensure that their clients had access to the necessary devices so they could access the services being offered. Some programs found creative ways to leverage existing resources or submitted grant applications for funding to purchase devices to loan or give to clients. One program partnered with a local community college system to get clients access to the college's existing laptop loaner program. To help address the challenge of broadband access among clients in rural areas or those without broadband at home, some programs loaned out Wi-Fi hotspots. Others created public Wi-Fi zones in their office parking lots that clients could use to get online.

4. Holding Virtual Job Fairs

Program staff members observed that many employers, including small businesses, were using virtual job fairs to connect with job seekers, rather than relying solely on the online job application process. So some programs participated in and organized virtual job fairs to help connect clients and employers. One local workforce development board even built a new website to host virtual career fairs, where employers could connect directly with job seekers and conduct on-the-spot online interviews.

Program staff members said that many clients felt more comfortable asking questions in a virtual forum and enjoyed the ease and flexibility of attending job fairs online. Virtual job fairs offered flexibility to employers as well and made it easier and less expensive for them to participate. The format also offered employers additional benefits, such as a wider geographic pool of job applicants, improved attendee tracking, and streamlined job application management.

5. Allocating Adequate Resources to Train Staff and Support Digital Services

When reflecting on the future of virtual job search and the services provided to support it, many program staff members discussed two needs. First, some programs were able to spend time adapting their existing services and providing extra support to clients because the pandemic freed up some staff time. For example, human service agencies experienced reduced workloads because federal workforce participation mandates were temporarily lifted. As workloads returned to pre-pandemic levels, the challenge, they said, would be to make time to continue providing this support. Second, some programs expressed the need for sustainable sources of funding to support digital device loans. As described above, many clients were not able to access virtual services because they did not have devices at home or shared their devices with other people in their households.

Summary

Overall, workforce program staff members were excited about the opportunities virtual job search presented and the service adaptations their programs made to reflect the changing hiring landscape. Virtual job search and the services provided to support it improved access for some clients and posed new challenges for others. Programs worked to mitigate those challenges and ensure equitable access, and they are eager to find sustainable solutions to continue this work in the future.