Helping Students Meet Basic Needs to Support Their Success

Implications for policy and practice:

- Address students’ basic needs using approaches supported by a growing evidence base. Students of color, students who are parents, and other historically marginalized students are most likely to struggle to meet their basic needs. Basic needs interventions should make a priority of these students and eliminate application barriers and eligibility restrictions that can prevent students with low incomes from receiving the support they need.

- Ensure that financial aid programs support nontuition costs and that emergency aid is readily available. Federal financial aid such as Pell Grants can be used to meet students’ nontuition costs and basic needs, but state and institutional financial aid sometimes cannot. All financial aid programs should make their funds available for nontuition purposes to help students reduce their unmet needs.

- Conduct more research on basic-needs interventions. There is emerging evidence on interventions that improve student basic needs security. However, more study of such interventions is needed, including further study of their equity implications.

There is widespread evidence that students in higher education have difficulty meeting their basic needs for food, housing, childcare, health care (including mental health care), transportation, and technology. Having inadequate access to these resources is known as basic-needs insecurity (BNI). When students cannot meet their basic needs, it interferes with their ability to concentrate on their studies, build social connections, maintain mental health, feel that they belong in college, remain enrolled, and eventually graduate. Investments in proven strategies to reduce students’ BNI can therefore help improve their chances of success. This brief explores the interventions that can help reduce BNI among students in higher education and the emerging evidence behind these interventions.

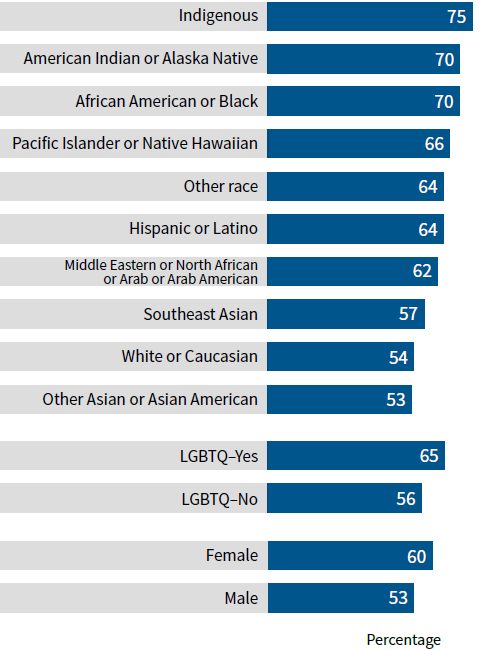

BNI exists at every institutional type and credential level, but rates of BNI are particularly severe at community colleges and among students of color. In a recent, nationwide survey of 195,000 students conducted in the fall of 2020, more than one in three (34 percent) of all students reported that they had experienced food insecurity and nearly half (48 percent) had experienced housing insecurity. An alarming 14 percent of all students reported experiencing homelessness. Black, American Indian, and Alaska Native students experience BNI at rates 16 percentage points higher than White students (70 percent compared with 54 percent) and other students of color also face very elevated rates of BNI, as shown in Figure 1. The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent inflation have also exacerbated racial and economic disparities and increased the costs of food, childcare, and transportation, making it even more difficult for students to meet their basic needs.

Figure 1. Percentages with Basic-Needs Insecurity by Racial and Ethnic Identity, LGBTQ Status, and Gender Identity

SOURCE: The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice, #RealCollege 2021: Basic Needs Insecurity During the Ongoing Pandemic (Philadelphia: The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice, 2021).

Reviews of the research on student BNI—including a landmark U.S. Government Accountability Office report on food insecurity—have confirmed the prevalence of BNI among college students. Research has also revealed significant equity gaps among groups of students facing multiple barriers to completing college. For example, parenting students, particularly single parents and parents of color, experience BNI at rates much higher than nonparents or White, parenting students. Students who attend historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) also experience high rates of BNI—with 67 percent of HBCU students reporting food or housing insecurity, compared with 58 percent of students nationwide at all types of institutions.

There is emerging evidence on interventions to reduce students’ basic-needs insecurity.

Some interventions seek to reduce students’ BNI by connecting them with various forms of financial support. One such approach uses “nudging,” which involves sending customized outreach to students about the availability of basic-needs resources, often by text message or email. A study at Dallas College evaluated the impact of customized text messages offering information about resources that also used intentionally supportive language designed to reduce stigma. This nudging increased the percentages of students who applied for emergency aid and who reached out to “benefits hubs,” where they could obtain information and case management for a range of public benefits and tax benefits.

Another study of nudging at Western Michigan University sent emails to encourage students to use food pantries. It found that the effort increased the proportion of students who remained enrolled by 12 percentage points and reduced the proportion who reported experiencing food insecurity. Another study of customized emails to students at Amarillo College found that the messages more than doubled the proportion of students who visited the college’s benefits hub. Recipients of the emails were also 20 percent more likely to pass developmental (remedial) education courses, though the study found no statistically significant impacts on longer-term measures of success such as course completion or grade point average.

There is also evidence that directly connecting students to public benefits and financial support may improve their success. The Single Stop model at community colleges screens students to determine whether they qualify for federal, state, or local public benefit programs and tax benefits and connects students and their families to additional services such as tax preparation, childcare, and immigration consultation. An evaluation of the model showed that it may improve persistence in college and academic achievement.

Providing emergency financial aid is another common practice to help students deal with unexpected expenses and reduce BNI. A preliminary evaluation of emergency aid at Compton College found students who received emergency aid quickly and with few administrative burdens were twice as likely to graduate as students who did not receive emergency aid (although the results vary depending on whether the student had financial need or was close to graduation). Students also report that emergency aid programs help them succeed: In a national survey, 69 percent of students who received federal emergency aid during the pandemic believed the extra funds helped them stay on track to graduate. However, the same survey showed that fewer than one-third of students experiencing BNI applied for and actually received emergency aid—a significant shortcoming in meeting students’ needs.

Other types of BNI interventions have sought to tackle specific student needs. For example, subsidies for transportation at Rio Hondo College in California have been associated with increased persistence, credit accumulation, and credential attainment. At Bunker Hill Community College in Massachusetts, a meal voucher program that allowed students to eat in the cafeteria for free several times per week was found to have a positive but modest impact on the number of credits attempted. Many institutions also attempt to provide access to affordable childcare for parenting students, but there have been fewer evaluations of these efforts.

Basic-needs support has also been a part of comprehensive reforms shown to improve student success, including the City University of New York Accelerated Study in Associate Programs and Washington State’s Integrated Basic Education Skills and Training program. Both provided students with support for nontuition costs, including public transit subsidies, free textbooks, and childcare assistance. However, it is difficult to isolate how basic-needs support influenced the overall success of these more comprehensive interventions.

Financial aid programs should cover costs beyond tuition and fees to help students meet their basic needs.

All of the programs and interventions that have shown some ability to reduce BNI address students’ expenses beyond tuition and fees. Nontuition expenses make up 80 percent of the total cost of attending a two-year public institution, and 61 percent of the total cost of a four-year public institution. Yet some state and institutional financial aid programs (for example, “last-dollar” programs that are only available after other aid has been exhausted) are limited to only covering tuition and fees. These programs are likely to be more successful at reducing BNI if they also make funds available to help students meet the nontuition costs that contribute to BNI, including food, housing, and childcare.

Basic needs programs should be easily accessible to students, with clear, simple application and eligibility-determination processes.

While a variety of public benefit programs exist to help narrowly defined populations meet their basic needs, those programs often have extensive eligibility rules that place “administrative burdens” on applicants and make benefits substantially more difficult to obtain, particularly for people with low incomes. Financial aid programs and interventions to reduce BNI among college students should avoid onerous paperwork or application requirements and eligibility restrictions that could exacerbate equity gaps among students already experiencing disproportionate levels of BNI.

More research is needed to assess the impact of BNI interventions on equity and to build the evidence base.

Given that rates of BNI for students of color and other marginalized students are much higher than those of White students or nonmarginalized students, any effective, appropriately targeted intervention should logically begin to close equity gaps in BNI among students. However, data are not yet widely available to show how BNI interventions affect students in different subgroups, which prevents a full analysis of these interventions’ equity implications. Evaluations of interventions should contain data disaggregated by race and ethnicity whenever possible. Furthermore, evaluations of all types of interventions should measure the extent to which they reduce students’ BNI, in addition to measuring their impact on academic outcomes. Reducing student BNI is an independently positive outcome and can have positive effects on students’ family well-being.

State and federal policymakers seeking to make large investments in student success should fund promising BNI interventions—and evaluations of such approaches to help expand the evidence base. They should also make investments in proven comprehensive programs with enhancements to address basic needs. Additionally, high rates of BNI at HBCUs, Tribal Colleges and Universities, and other Minority-Serving Institutions mean that policymakers should set aside funding for interventions designed to promote student success and reduce students’ BNI specifically at those institutions. Since these institutions have historically been excluded from receiving state and federal resources, policymakers should waive requirements that can make it financially difficult for these institutions to gain access to these funds, for example requirements to provide institutional resources to “match” state and federal funding.

Additional Resources:

- #RealCollege 2021: Basic Needs Insecurity During the Ongoing Pandemic | The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice

- One-Stop Center Models: A Guide to Centralizing Students’ Basic Needs Supports | The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice

- Turning Basic Needs Assessments into Action | The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice

- Basic Needs Center Toolkit | California Community College Chancellor’s Office

- Opinion: Born of Necessity, Emergency Student Aid Should Become Standard Operating Procedure | Higher Learning Advocates

- Basic Needs Initiative | ECMC Foundation

Bryce McKibben is the senior director of policy and advocacy at The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice. He was previously the lead higher education adviser for Senator Patty Murray (D-WA), chair of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee.

Atif Qarni is the managing director of external affairs at The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice. He was previously Virginia’s secretary of education.