Improving Programs Using Students’ Voices

Lessons from the Los Angeles College Promise Program

The Los Angeles College Promise program aims to increase college access and success among students in the Los Angeles Community College District (LACCD) by offering on-campus support services and a scholarship that fully covers students’ tuition and fees during their first two years.[1]

The program has a large student population to consider, as it operates across all nine LACCD community colleges (which together serve over 200,000 students) and is available to all high school graduates in the Los Angeles Unified School District (the largest public school system in California and the second largest in the United States).[2] Like many postsecondary student success programs across the country, LA College Promise is making program changes to provide more effective support that helps students stay in school and graduate.[3] This brief highlights how in the past two years LACCD has:

- Established a cycle of continual program improvement across the nine participating colleges using tools and insights from the field of behavioral science

- Built its staff’s ability to draw on a critical but often neglected source of information in this process: the students themselves

The Cycle

Establishing a Cycle of Continual Improvement

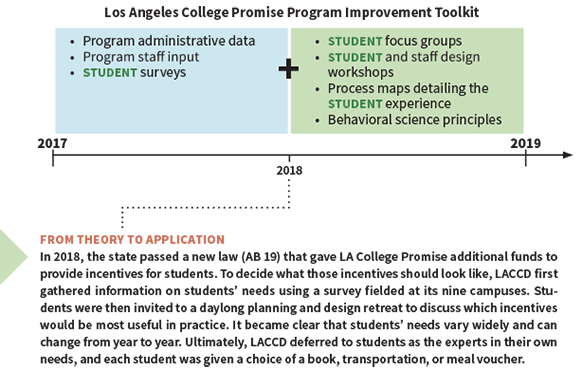

In 2017, LACCD partnered with MDRC to (1) assess the Los Angeles College Promise program’s first year of implementation and (2) establish an effective cycle of continual improvement rooted in the diagnosis and design practices employed by MDRC’s Center for Applied Behavioral Science. Over the course of two years, staff members from LACCD and its nine colleges were trained to identify challenges preventing students from meeting program goals, diagnose the causes of each challenge, and ultimately design solutions that serve students’ needs.

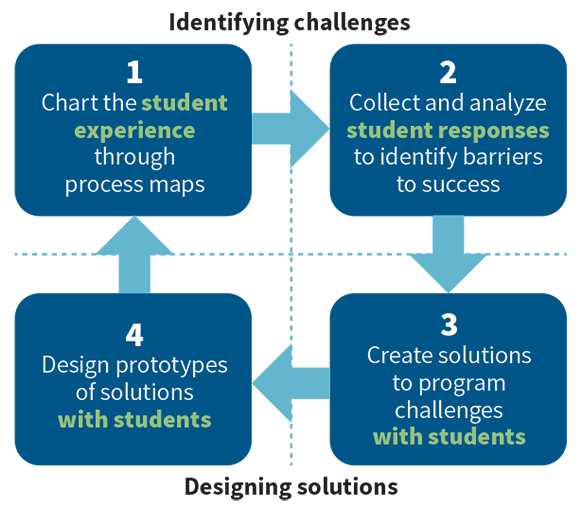

Staff members from the district and each college embraced the student-centered cycle outlined in the graphic to the right, as well as the use of process maps (visual tools that represent the steps of processes from start to finish, often used to identify opportunities for improvement). Other student success programs looking to reimagine their improvement cycles and expand the ways they engage students can use these strategies as a general guide.

By giving college staff members the resources to understand and apply each step in this cycle, LACCD fostered a culture of creative and effective continual program improvement.

Involving Students

Including Students’ Voices: Moving Beyond Surveys

The Foundation for California Community Colleges’ Vision for Success directs colleges in the state to design services, programs, and policies with students in mind. Thus, LA College Promise’s move to make students central players in program improvement was a necessary step not only to serve its students effectively, but also to align the program with system-wide priorities.

In its initial year, LA College Promise gathered students’ opinions through surveys. Though those surveys provided important information, they did not fully capture the diverse voices of the program’s large student population. LA College Promise has since gone further, engaging students in multiple ways at every stage of the continual improvement cycle.

Lessons Learned

Learning from Students’ Voices

The Center for Applied Behavioral Science at MDRC emphasizes it is important to use both quantitative and qualitative data to diagnose the factors preventing students from succeeding. In 2019, to engage students and uncover potential areas for program improvement, LACCD and MDRC held student focus groups at all nine LA College Promise colleges. MDRC used a process map of the LA College Promise program to guide discussions in 16 focus groups with a total of 87 students. The focus groups produced information about barriers to success that the program was helping students overcome, and about barriers yet to be addressed. This information helped the colleges determine what challenges should be their top priorities during the 2019-2020 school year.

The findings illustrate that students’ experiences vary widely, and that to understand their many needs and address them comprehensively, programs must gain insight from as diverse a group as possible. Focus group findings were presented in May 2019 at a full-day meeting attended by LACCD college representatives and students, where staff members were given a chance to brainstorm potential program improvements and solutions alongside students (steps 3 and 4 of the cycle illustrated on page 1).

The table below describes some of the topics discussed during the focus groups, the insights students shared, and related lessons that could be pulled from the findings. It exemplifies what valuable information programs can obtain if they give students meaningful ways to engage in program improvement.

According to Los Angeles College Promise Students:

| TOPICS | WHAT IS WORKING? | WHAT COULD IMPROVE? |

|---|---|---|

|

Topic:

Incentives

|

What Is Working?

The transportation benefit (a Metro U-Pass) made commuting to school easier and allowed students to redirect funds they would have spent on transportation to cover other expenses, such as food. “Thanks to [LA College Promise] I was able to acquire a U-Pass, which essentially allows me to commute from here to my home without having to pay the additional expenses for the commute itself. And that’s also helped me save a lot of money that I can now use to buy books or even lunch.” |

What Could Improve?

The $150 book voucher does not cover all costs. While many students find suitable work-arounds such as renting or borrowing books to reduce this expense, the cost of required online access codes kept students from having access to classroom materials and assignments. “The fact with me right now is that I haven’t been able to do my chemistry homework, just for the fact that I need to get money for the [online course] account.” |

ImplicationsStudents appreciate the benefits offered by LA College Promise, but those benefits do not always cover all costs. The College Board estimates a full-time student at a community college needed $1,440 to cover books and supplies for the 2018-2019 academic year.[4] Programs should make a priority of partnerships with community stakeholders that can provide students with more resources. For example, thanks to the partnership the program has built with the mayor’s office, LA College Promise will offer laptops to program students next year. |

||

|

Topic:

Sense of Community

|

What Is Working?

Peer mentorship, student events hosted by the mayor, and study-abroad opportunities all helped students develop a sense of community. “I have had a lot of positive mentorship and role modeling that has like been one of the biggest things that I’ve gained from the program. Not only with my peer mentor in that first year, but especially after that first year once I started meeting more people: administrative representatives of the program and then also people at [my college]. That has really helped me kind of like set my foot at [my college].” |

What Could Improve?

A lack of dedicated space at some colleges for Promise staff members and students to meet is making it harder to create a community centered on the Promise program. “The thing is that, I don’t think that you really can tell which one is the Promise program counselor and which one is the regular [counselor].... They are all the same.... So we just go [to] whatever they give us.” “[Promise] should have their own office and their own counselors.” |

ImplicationsFostering a sense of belonging among students can make it more likely they will stay in school.[5] On many campuses, space is a limited luxury and programs have not addressed the implications of lacking dedicated space. While there are a variety of ways for programs to build strong communities, a direct way to do so may be to find or repurpose physical spaces where students and staff members can connect. At a recent retreat, LACCD staff members decided to make a priority of finding a designated space for Promise students at each campus during the 2019-2020 academic year. |

||

|

Topic:

Program Requirements

|

What Is Working?

Requirements that push students to meet with coaches helped them stay on track. “With my coach, I just talk about my goals and stuff.... She knows how it is and she gives really good advice. Say if I lose motivation in my classes and feel like I can’t do it, she is very [good at] pushing me to being on track.” |

What Could Improve?

While students understand the benefits of full-time enrollment, that requirement is the hardest for them to meet. “Maintaining full-time [enrollment is most challenging to keep up with]. I know many of my classmates ended up dropping first semester because they were going through something at home or they would just [start] working and it was just really hard to catch up while they were working full time and going to school full time.” |

ImplicationsMany high-needs students have competing responsibilities such as taking care of dependent family members or working full time. Even younger students can have such responsibilities. Programs must weigh the importance of keeping students accountable against the need to give them flexibility, and work with students on strategies to keep them on track while juggling competing demands. LA College Promise’s appeals process acknowledges this tension and allows staff members to waive requirements for students facing extenuating circumstances. |

||

|

Topic:

College Accessibility

|

What Is Working?

Some students attribute their decision to go to college and their ability to avoid student debt to the LA College Promise scholarship. “I wanted to say that I’m very thankful for this program because it puts a lot of relief on me. I work, but I know that I don’t need to work full time because I’m not paying for my tuition. And if I was paying for my tuition, I would just be questioning why I am in class the whole time.... The fact that I know that I’m not going to need to pay through the LA Promise is one of the main reasons why I’m here.” |

What Could Improve?

The persisting stigma about going to community college can create major barriers to college access. Pressure against the decision to go to community college can come from peers, teachers, advisers at high schools, and parents. “[The counselors] were more actually upset about students going to community college than going to USC or Cal States. Because they kept saying that our school is based on high reputation. That we graduated from here and we’re going to the top colleges — we’re going to these colleges, we’re not going to no community |

ImplicationsStudent success programs should continue to strengthen connections with staff members at high schools and actively try to change the conversation about community college. Many programs, including LA College Promise, send staff members to local high schools to give presentations about those programs and the option of going to community college. Colleges should consider additional strategies to change the perception of community college while ensuring that students are well informed and supported in making their college decisions. |

||

Funders

MDRC would like to thank the Los Angeles Community College District for its support of this work. The partnership between MDRC and LACCD also greatly benefited from the concurrent efforts of MDRC’s College Promise Success Initiative, funded by Ascendium Education Group.

[1] According to LACCD, the Los Angeles College Promise program helped build statewide support for AB19 and AB2, state laws that make the first two years of community college tuition-free across California.

[2] To learn more about the program and the students it serves, visit lacollegepromise.org.

[3] District administrators measured a fall-to-spring-semester full-time persistence rate of 71 percent for students who entered the LA College Promise program in 2017.

[4] College Board, “Average Estimated Undergraduate Budgets, 2018-2019” (2019, website: https://trends.collegeboard.org/college-pricing/figures-tables/average-estimated-undergraduate-budgets-2018-19).

[5] Leslie R.M. Hausman, “Sense of Belonging as a Predictor of Intentions to Persist Among African American and White First-Year College Students” (Research in Higher Education 48, 7: 803-839, 2007).