Multiple Measures Assessment and Placement Promotes Community College Student Success

Implications for policy and practice:

- Expand placement practices to include the use of multiple measures assessment (MMA) to place students in developmental (remedial) courses. MMA is more accurate than tests alone (the main method colleges use now for developmental placement), with high school grade point average (GPA) being the best available measure for predicting college success. Increasing access to college-level courses in the first semester using MMA increases the percentage of students who complete those courses, with positive effects on all major demographic subgroups.

- In implementing MMA policies, ensure institutions have the technical and human resources capabilities to obtain and manage multiple measures data. When colleges cannot obtain high school transcripts electronically, they can obtain them from students. Testing and advising departments may need to hire additional staff members or provide additional training to transition to MMA systems.

- Include faculty members and administrators in MMA decisions and make sure students have a clear understanding of the institution’s placement approach. Involving faculty members will get them invested in the success of MMA and thereby strengthen MMA implementation.

- Plan communications with students. Well-planned communications with students about placement criteria are also important to successful MMA implementation.

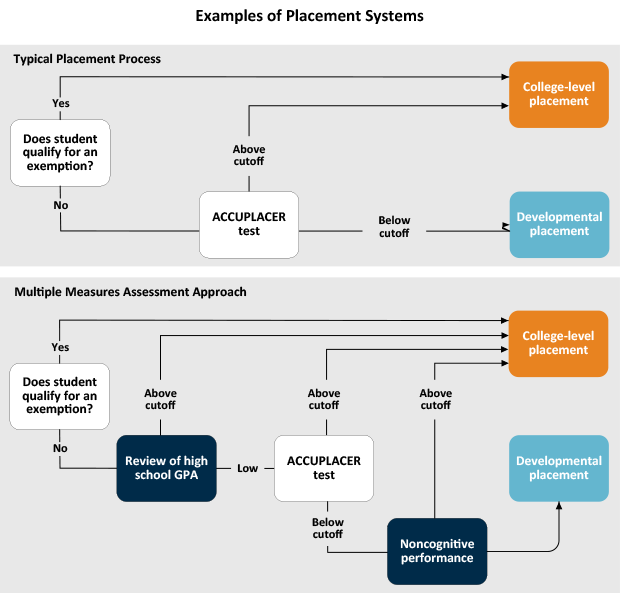

While most community colleges admit all students who apply for admission, the vast majority have required students to demonstrate specified levels of literacy and numeracy before they can take college-level courses. Typically, students have been assessed using a single placement test, such as the College Board’s ACCUPLACER. Colleges—or sometimes states—choose cutoff scores on the assessment. Students who score below the cutoff are not considered to be “college-ready” in the relevant subject area and are referred to remediation through developmental education courses. Research shows that placement tests alone do not adequately determine which students need remediation, and that they misplace many students into developmental courses who could be successful in college-level courses in the subject. As a result, many students must spend time and money on courses that they do not need.

Colleges are therefore seeking more reliable and equitable ways of assessing student readiness for college courses. One approach is to use additional indicators of student preparation, such as high school records, noncognitive assessments that examine behaviors and attitudes, background questions, or other test results. These indicators can be used in conjunction with or in lieu of placement tests.

Multiple measures assessment (MMA) is more accurate than tests alone.

Researchers and policymakers have been interested in understanding whether MMA yields placement determinations that lead to better student outcomes than a system based on placement test scores alone. The best evidence comes from randomized controlled trials that were conducted in institutions in Minnesota, New York, and Wisconsin.[1] Students who were bumped up into college-level courses by the MMA placement systems (using cumulative high school GPA along with placement tests and other available measures) were more likely to reach important college milestones than their control group counterparts. Among bumped-up students, enrollments in college-level math and English courses were between 15 percentage points and 30 percentage points higher, and completions (grades of C or higher) were between 10 percentage points and 15 percentage points higher. Predictive analyses performed with data from these studies also consistently found that high school GPA was the measure that did by far the best at predicting success in college-level courses.

MMA could increase the numbers of students of color and students from low-income backgrounds completing college-level courses. But MMA alone will not eliminate disparities.

The majority of students at community colleges take developmental courses, as do a large percentage of students at four-year colleges. Black and Latino students and students from families with low incomes are disproportionately likely to be in developmental education.[2] MMA has the potential to increase the number of these students enrolling in and completing college-level courses as it is adopted by more states and colleges across the country. The randomized controlled trials mentioned above revealed positive effects on college-level course enrollment for students of all races, ethnicities, and genders, and for recipients and nonrecipients of Pell Grants. Most subgroups also saw similar effects on the percentages of students who completed those courses, although findings for men and students of color differed slightly across subjects and studies.[3] The positive effects on enrolling in and completing introductory, college-level English and math courses are important, as they put students one step closer to degree completion, but MMA will not eliminate disparities in degree attainment by itself.[4]

MMA is being implemented nationwide.

MMA is being adopted by a number of states and systems of higher education. Descriptive evidence from states such as California, Massachusetts, and North Carolina also points toward improvements in access to and completion of college-level courses.

- California mandated MMA and placed more students directly in transfer-level math and English—courses with credits that can be used to transfer to four-year colleges. These changes appear to be related to substantial increases in transfer-level math and English course completion, especially among students of color.

- Massachusetts adopted a three-pronged approach to transform developmental education, including the use of MMA. Reports from a pilot study indicate increased enrollment in and completion of transfer-level math courses.

- North Carolina provided developmental education exemptions for high school graduates meeting certain GPA criteria. Descriptive evaluations report increased access to and success in college-level courses.

Several other states have also implemented MMA, including Indiana, Texas, Virginia, and Washington, which defaulted to MMA due to the COVID-19 pandemic and cancellation of standardized testing. Research is needed to evaluate whether these changes improved student success.

The effectiveness of MMA hinges on successful implementation.

There are a number of challenges that should be addressed when designing, enacting, and expanding MMA policies. The following steps are recommended.

- Gauge how ready the institution is for a shift to MMA:

- Assess staff views of MMA.

- Review the research on MMA and disseminate the research among stakeholders to get them invested.

- Determine the institution’s technical ability to obtain and manage MMA data such as high school transcripts or self-reported GPAs.

- Assess academic advising and counseling resources and capabilities.

- Include faculty members, other staff members, and administrators at all stages of MMA policy making and planning, so they feel invested in the change.

- Take steps to ensure students are aware of and understand MMA policies.

- Remember that MMA will not close all equity gaps alone. It should be paired with other strategies, such as corequisites, which require that students receive additional support if they enroll in college-level courses. (Stay tuned for an upcoming brief on corequisite remediation.)

Multiple measures are now used in over half of states to assess and place incoming community college students, and the research on this practice points toward significant benefits for students. Using multiple measures in lieu of or in addition to placement testing expands access to the college-level courses required for degree completion. In fact, students not only gain access to the courses, they succeed in them, meaning they are more likely to achieve their postsecondary goals. MMA is already improving student outcomes, but institutions will also need to incorporate other strategies to further close equity gaps. Nevertheless, MMA can be a critical part of reform efforts.

Additional Resources:

- Toward Better College Course Placement | MDRC

- Rethinking College Course Placement During the Pandemic | MDRC

- Examining Reforms in Postsecondary Student Placement Policies | Research for Action

[1]MDRC and the Community College Research Center (CCRC) at Columbia University have now performed two rigorous studies of MMA. The first, funded by the Institute of Education Sciences through the Center for Postsecondary Analysis, included seven community colleges from the State University of New York system. The second, funded by the Ascendium Education Group, took place at four Minnesota colleges and one Wisconsin college.

[2]The United States Census defines Latino (masculine) or Latina (feminine) as any person of “Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin.” In recent years, some research publications and other sources have started using “Latinx” as a gender-neutral reference to this population. See Andrew H. Nichols, A Look at Latino Student Success: Identifying Top- and Bottom-Performing Institutions (Washington, DC: The Education Trust, 2017).

[3]Barnett, Kopko, Cullinan, and Belfield found significant positive effects on college English course completion among men and students of color, but no significant effect on math completion. Cullinan and Biedzo found significant positive effects in both subjects among students of color. See Elisabeth A. Barnett, Elizabeth Kopko, Dan Cullinan, and Clive R. Belfield, Who Should Take College-Level Courses? Impact Findings from an Evaluation of a Multiple Measures Assessment Strategy (New York: Center for the Analysis of Postsecondary Readiness, 2020); Dan Cullinan and Dorota Biedzo, Increasing Gatekeeper Course Completion: Three-Semester Findings from an Experimental Study of Multiple Measures Assessment and Placement (New York: MDRC, 2021).

[4]MDRC and CCRC have received funding to estimate effects on graduation rates among students in the New York and Minnesota/Wisconsin trials. These findings will be published starting in 2023.

Federick Ngo is an assistant professor of higher education at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. His research examines higher education policy, with a focus on college access and success for community college students.

Dan Cullinan is a senior associate in MDRC’s Postsecondary Education policy area. He leads Multiple Measures Assessment projects, evaluating and scaling alternative placement systems that use multiple measures in addition to tests.