More Tutoring Lessons from New Mexico

How the Shift to an In-School Model Expanded Access and Improved Attendance

While there is ample evidence that intensive or “high-dosage” tutoring has positive effects, the knowledge base for expanding that support to additional students remains limited. To learn more, the Personalized Learning Initiative (PLI), a collaboration between MDRC and the Education Lab at the University of Chicago, partners with school districts around the country to implement and evaluate a range of alternative tutoring models, such as virtual rather than in-person tutoring, tutoring with smaller student-teacher ratios, and tutoring that makes use of educational technology platforms. The goal is to assess which models work best for which students in which contexts, to improve learning across the board.

This issue focus shares implementation lessons from the 2023–2024 school year in New Mexico, following a previous publication that discussed the challenges the New Mexico Public Education Department (NM PED) experienced rolling out a preliminary tutoring model statewide for the 2022–2023 school year. Developed in partnership with PLI and Saga Education, an independent, nonprofit tutoring organization, the original model was designed to address staffing challenges in rural parts of the state and focused on providing virtual math tutoring for ninth-grade students outside school hours, in the evening or on weekends. NM PED had funds to serve 500 students and opened the application process to all ninth-grade students in New Mexico. Several thousand were eligible, but the state didn’t even receive 500 applications and was able to match only 300 students with tutoring—1.5 percent of those eligible.

In response to the low participation rate, for the 2023-2024 school year, NM PED, in continued partnership with PLI and Saga, shifted the timing of virtual tutoring to occur during the school day and to focus on middle school, with dramatic results: attendance rates were extremely high in the schools where the program was offered. Of the 471 New Mexico students assigned to tutoring, 90 percent attended at least one session, a substantially higher rate of participation than that seen in other recent studies. For example, Brookings reports that only 19 percent of targeted students in California’s Aspire Public School received on-demand virtual tutoring, and a recent study of Nashville’s in-school, in-person tutoring initiative found that only 25 percent of targeted students actually met with a tutor.

Virtual models are of particular interest for rural locales—like much of New Mexico—given the limited access to tutors in smaller and more remote communities. New Mexico’s successful implementation offers policymakers and practitioners insights for expanding access to tutoring and improving attendance under similar restrictions.

Characteristics of New Mexico’s Virtual Model

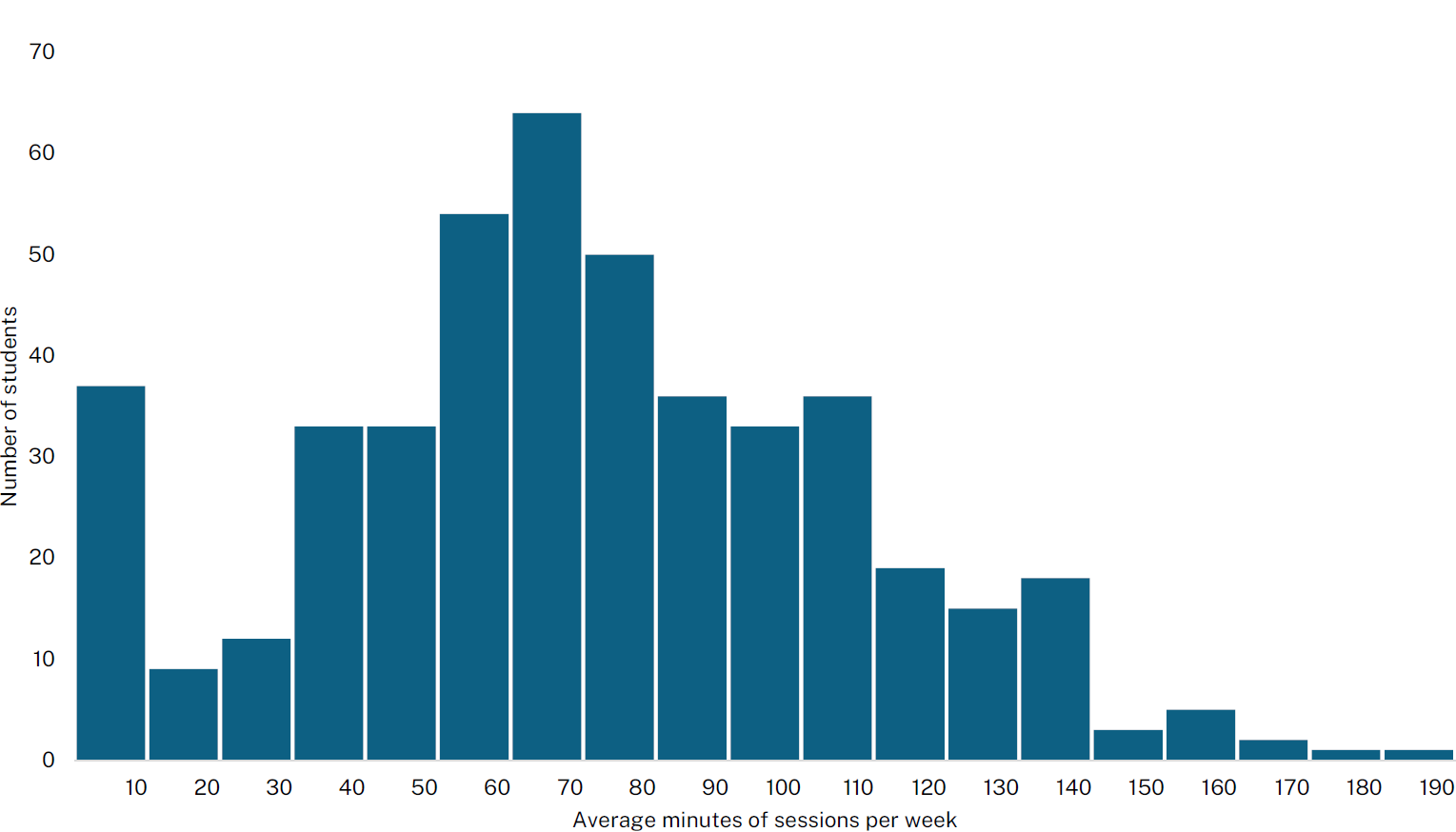

Virtual tutoring for New Mexico’s 2023–2024 school year was delivered in-school, grade-wide, and with facilitated tutor-teacher communication. As shown in Figure 1, under this revised model, the average New Mexico student attended 2.14 tutoring sessions per week, receiving 71 minutes of tutoring.

Figure 1: Distribution of Average Minutes of Tutoring Sessions per Week

SOURCE: University of Chicago Education Lab internal analysis.

Students logged into their virtual sessions during a dedicated tutoring class in their regular school schedule overseen by a live proctor.

Partner schools embedded tutoring in the school day by creating designated tutoring classes. A proctor was assigned to ensure that students showed up, logged into devices, and stayed engaged in tutoring. The proctor was often the school’s math teacher, or sometimes an education assistant or another subject-area teacher.

All students in a grade received tutoring.

Since all students in a grade or class participate, the model avoids some students being sent away for tutoring while others engage in traditional classroom work, electives, or what may be considered more desirable activities. Thus, grade- or class-wide tutoring can potentially lessen negative stigma or a sense of exile or loss.

The benefits of grade-wide tutoring in the small schools that are typical in rural New Mexico could prove a solution to the scheduling problems noted in other programs being evaluated by PLI. Many of the New Mexico partner schools were small enough for all students in a grade to be in the same core classes, which allowed them to receive tutoring at the same time. The average grade size in schools in this study was 22 students.

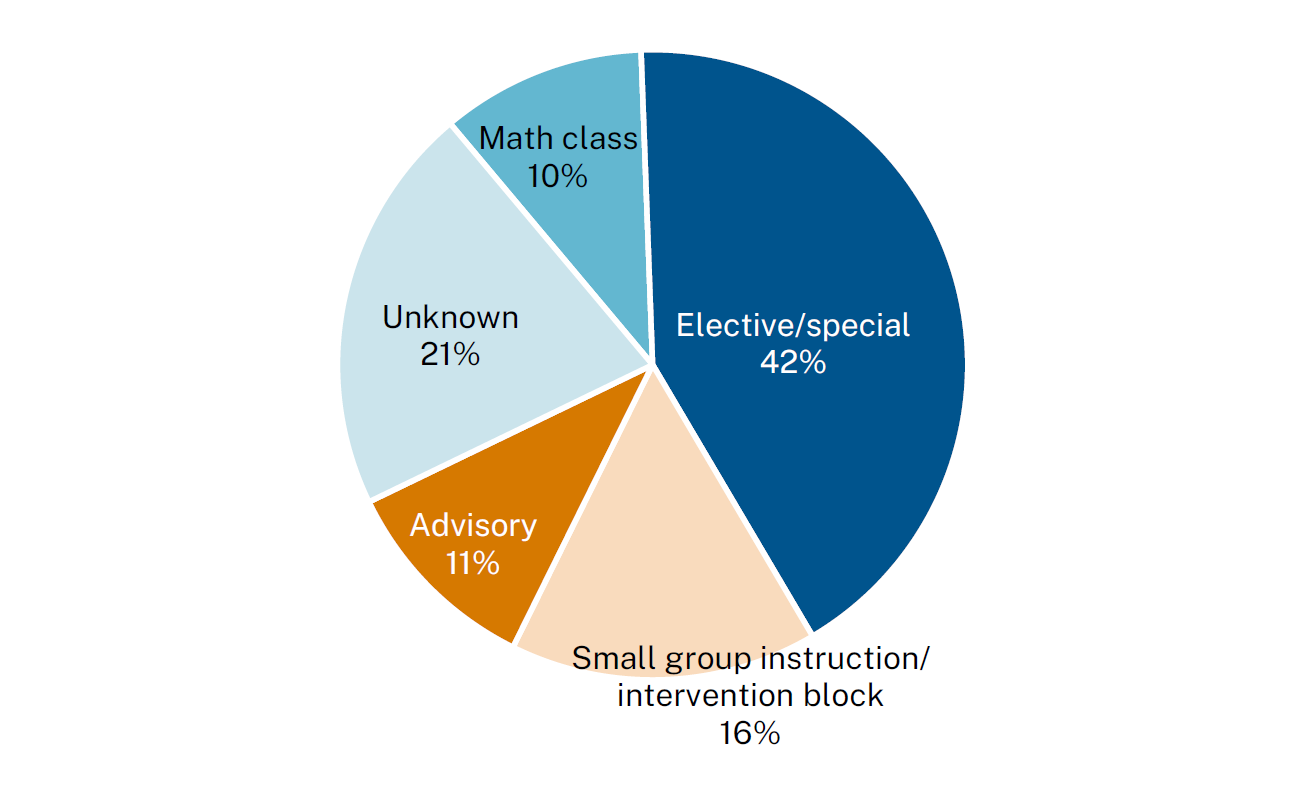

School leaders most often repurposed electives or other special coursework to make room for tutoring.

One major point of consideration in building tutoring into the school day is finding the time. Here again, the all-grade-level model helped alleviate this challenge in New Mexico. Some partner schools designated a new time slot for tutoring, while others repurposed existing classes (generally electives or other special courses). As seen in Figure 2, about half (52 percent) of the PLI partner schools in New Mexico opted for the latter: 42 percent repurposed electives or special courses, and 10 percent repurposed math classes.[1] The remainder used advisory time or a math period’s existing small-group instruction or intervention block or a combination of the two.

Figure 2: Classes that Tutoring Replaced Across All New Mexico Partner Schools

SOURCE: PLI New Mexico site visit debrief forms.

The PLI Technical Assistance team noted that scheduling can present a dilemma when the only option for in-school tutoring is to replace electives or special courses that can be one of the main sources of student enjoyment at school and are often the only opportunity for students to interact with the arts and with community organizations. Ultimately, though, all New Mexico partner schools decided to make tutoring the priority given how important staff members believed it was for their students to improve their math skills.

Students could be quickly reassigned when tutors were unavailable.

Tutor absences are a major reason for students in all PLI partner schools to miss tutoring sessions. Under New Mexico’s revised model, all students received tutoring at the same time, which made it easier for students to join another group’s virtual session if a tutor was absent.

Schools encouraged flexibility.

Virtual tutoring in New Mexico allowed for flexible classroom implementation as it wasn’t necessary to group students together physically. Teachers were empowered to arrange their classrooms as they saw fit, and in many cases, students were seated randomly or intentionally not by tutoring group. Likewise, proctors were able to place students in a way they believed would facilitate their learning, which could mean separating students who were distracting one another or seating those who needed more encouragement near the proctor. The Google Classroom platform made it easy for tutors as well as proctors to see what students were doing in the tutorial.

The program included a log of communications between virtual tutors and teachers.

When tutors are not physically present in the school, it can be difficult for them to communicate with their students’ teachers. To mitigate this issue, NM PED developed an online log to facilitate tutor-teacher and tutor-teacher communication. (Figure 3 shows an example.) The first two columns in the log allow teachers to easily share daily lessons with tutors. The next column enables tutors to readily update teachers on individual student progress, with a final column for teachers to respond.

Figure 3: Illustrative Example of Tutor Communication Log

| Amazing Middle School Tutoring Group A3 Mondays, Tuesdays, and Thursday 9-10am Tutor: Carlos Ramirez | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Saga Curriculum Lesson | Tutor Notes | Teacher Response |

| 9/18/23 | F 2.4 Adding and Subtracting Fractions | Joel and Keira asked if they could go over operations with fractions because they got a bit confused when fractions came up when used in combining like terms. Today we went over some examples. | Please focus on practice problems at the next session. |

| 9/19/23 | F 2.4 Adding and Subtracting Fractions | Today we did some practice problems. Some already had the same denominator so they only had to add/subtract while others they had to solve for the LCM and then add/subtract fractions. Overall they did a good job. Tomorrow we will go over the answers. | Thank you for seeing a need and acting on it! I really appreciate it. |

| 9/20/23 | F 2.4 Adding and Subtracting Fractions | Today Keira got the opportunity to finish up her practice problems and we started going over the answers. Lucia was not present today. | Thanks Lucia is sick but should be back next Monday. |

| 9/21/23 | F. 2.5/2.6 Multiplying and Dividing Fractions | Today we started working on Multiplying and dividing fractions. Students did not know what reciprocal was so I went over that vocab. word and went over some examples for both mult./dividing | I will continue to reinforce reciprocal in class - thanks for flagging this. |

Looking Forward

Analysis of the impact of virtual tutoring in New Mexico on math test scores is in progress. While awaiting the impact report, NM PED is extending its partnership with PLI and Saga to continue providing this type of tutoring for New Mexico students for the 2024–2025 school year, based on the strong attendance to date. While the PLI study will not disentangle what features of the virtual model led to improved attendance, New Mexico’s overwhelming experience was that students received far more tutoring with the shift to an in-school model. Schools were able to find the time to provide proctored, virtual tutoring to all students in a grade and facilitated communication between tutors and teachers, resulting in students receiving a substantial amount of personalized math instruction. A virtual, in-school model like New Mexico’s may be one way that rural school districts or districts struggling with staffing shortages can still provide high-dosage tutoring.

[1] Schools that repurposed math classes typically took what would have been whole-group instruction with a classroom teacher and instead used the time for tutoring.