Show, Don’t Tell, Part 1

Using Nudges to Reach Program Goals

In their book “Nudge,” economist Richard Thaler and legal scholar Cass Sunstein unpack one of behavioral science’s most powerful precepts. Nudges are powerful environmental cues that influence people’s decision making, but without forcing a specific choice or restricting their options. Once you start looking for them, you’ll see nudges everywhere.

Sunstein and Thaler used the example of a high school cafeteria layout to demonstrate how small changes in our environment can influence our behavior, and we’ve discussed how a well-laid out office space can improve program participation rates. The example and our observations inspired MDRC’s Center for Behavioral Science (CABS) to create an interactive training session on the power of physical space to provide nudges. We asked training participants — staff at workforce development programs that help people find and keep employment — to try organizing their space with different goals in mind by designing a hypothetical high school cafeteria. Workshop participants received paper cut-out icons for all the essential materials — salads, hot food, snacks, desserts, beverages, cash registers, tables — and were asked to organize a logical cafeteria environment.

But the directions had a catch. Each group received a unique goal: arrange the materials to maximize either:

- Healthy eating,

- Profits, or

- Efficiency.

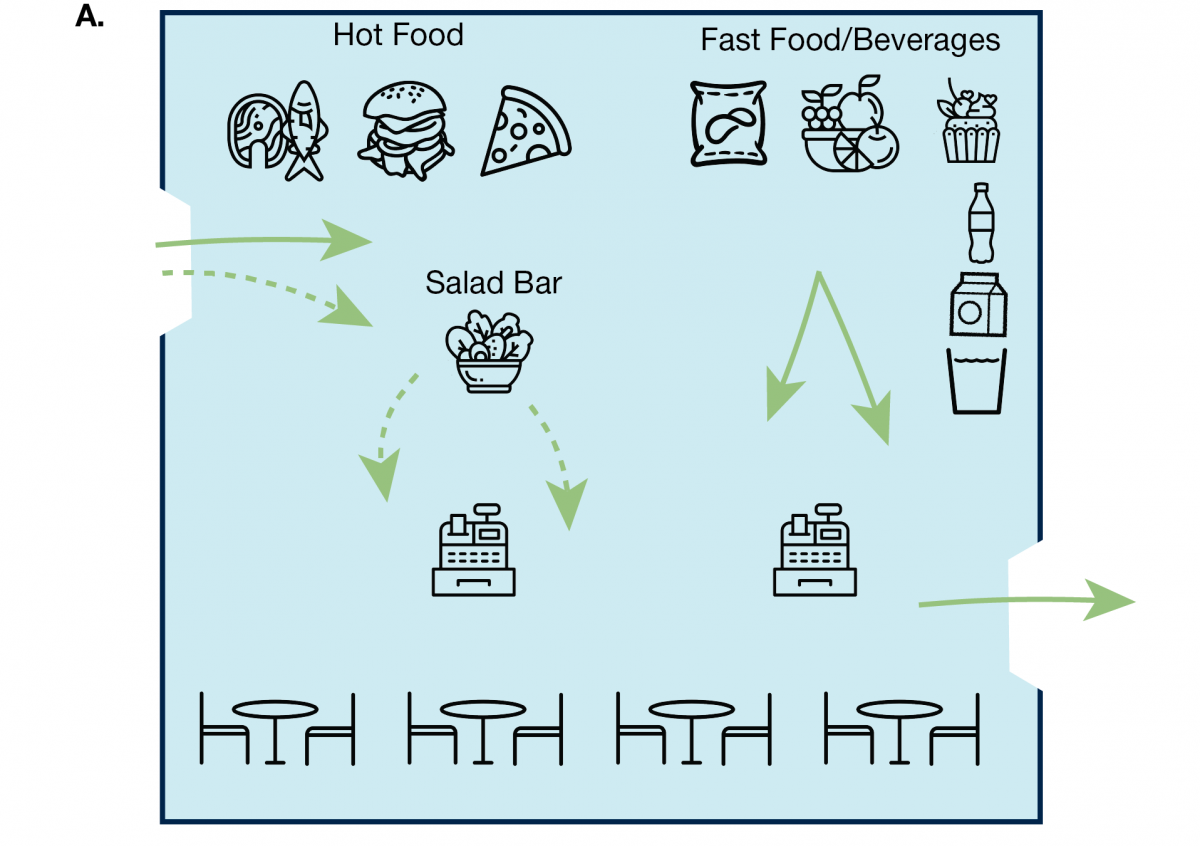

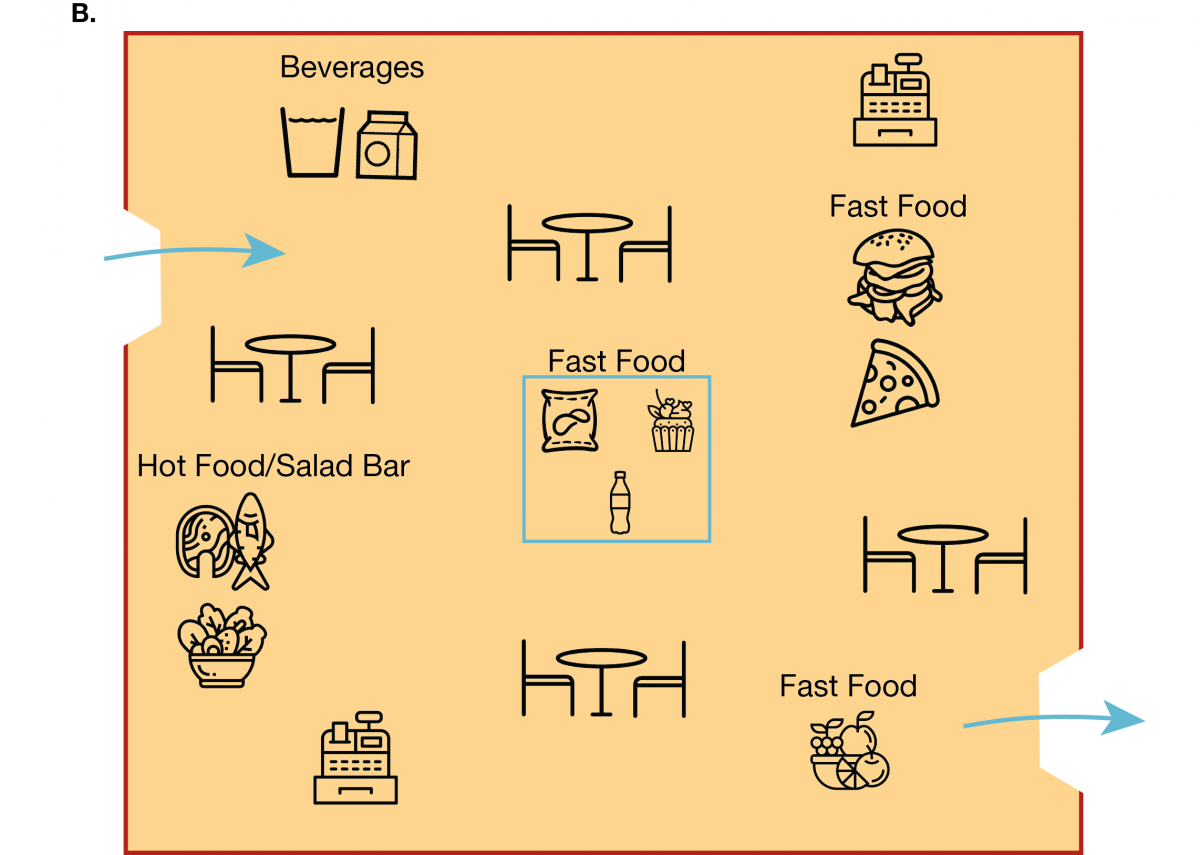

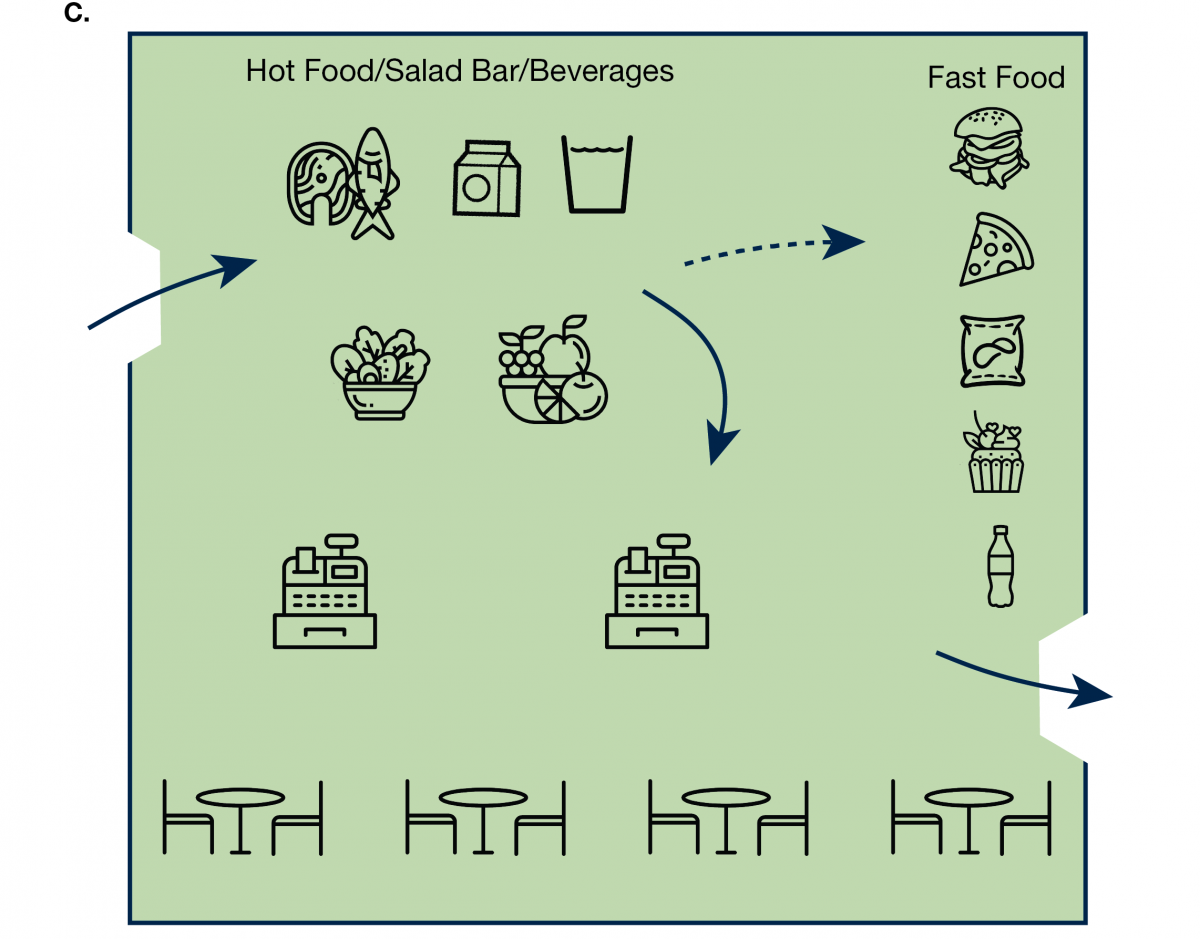

Look at Designs A, B, and C. Can you tell which design was intended to promote which goal?

Let’s look at the results.

Design A is all about efficiency. The food and drinks are organized neatly, with multiple paths to the cash register. In Design B, the aim was to maximize profits. Every time a student moved around the cafeteria, they would pass by a food item and be tempted to buy it. In Design C, the staff worked to maximize healthy eating. They put healthy food first, making it the most accessible and obvious choice. They went even further, hiding the unhealthy food against the wall, outside the normal flow of the cafeteria.

Workshop participants completed the exercise and noted three main takeaways from this activity:

1) Humans are intuitive designers. Workshop participants demonstrated an intuitive sense of how certain cues would influence behavior, without any discussion of behavioral science and design. This was largely based on their own experiences and preferences. Participating in this simple warm-up exercise helped them apply their intuitive sensibilities to create the right cafeteria for each goal.

2) There is no such thing as a neutral design. In social service settings, consider the first thing visitors see on a program website, or what a client encounters when they step into a waiting room for the first time. Is your program funding tied to the number of reported visits to your office each month? It’s easy to design your reception space to help you track return visits — a strategically placed sign-in station inside your entrance could further this goal, for example. Environmental cues can have a strong influence on clients’ decisions.

3) Be intentional in your design choices. The participants in our training worked on using design to advance their program goals, whether those meant changes to physical layouts, participation processes, or added methods of staff support. They went on to identify program challenges, diagnose behavioral barriers, and create solutions. These solutions took all shapes and sizes. For example, one participant developed a social media-based “buddy system” where clients could tag a friend to join them on a virtual tour of an in-demand career training to increase engagement in a new service. Another group of participants drafted a text message campaign to remind clients of upcoming meetings, with links to the location and the relevant enrollment information. These solutions helped link the processes of their programs to goals of client engagement, attendance, and ultimately, sustained employment.

Make intentional design work for your organization! Nudges exist everywhere. By recognizing the cues in your program processes that may be influencing participants’ actions, you can intentionally redesign those processes to do a better job of advancing your program’s goals. A complicated enrollment form may discourage completion, while a well-lit room may leave a good impression and encourage participants to return to your program. If you have any role in structuring the environment in which participants or staff make choices (and chances are that you do!), you can influence your program’s ability reach its goals.