Show, Don’t Tell, Part 2

Strategies for Creating Nudges Through Program Design

In last month’s post, we explored the idea that program design is not neutral: the way staff organize office space, service flows, intake forms, and other processes influences participants’ decisions, and by extension, your program outcomes.

Behavioral science theory tells us that all program environments have cues that influence decision-making and behavior without forcing a decision or restricting options – what behavioral scientists call nudges. The idea is that the environment influences a person’s behavior. There are many ways to incorporate nudges into program design, beyond just changing environmental cues, to advance your goals. This post shows how programs can be intentional about changes to procedures – through outreach, the flow of services, and staff-client interactions – to help staff and participants reach their goals.

Define Your Goals

Before you begin experimenting with different design options, be clear about your organization’s goals for its participants. Are they specific enough to measure, and sufficiently targeted to help participants achieve them?

Before you begin experimenting with different design options, be clear about your organization’s goals for its participants. Are they specific enough to measure, and sufficiently targeted to help participants achieve them?

For workforce development programs working with underemployed or unemployed individuals to find lasting jobs, participant goals might be:

- Attend an interview skills workshop

- Meet with career counselors at least once a month

- Finalize a resumé

In our work with programs, we often find that they want to improve engagement in three areas: getting people in the door, removing roadblocks to program completion, and building positive interactions. The Center for Applied Behavioral Science (CABS) at MDRC has used randomized control trials to evaluate whether behaviorally informed design strategies in these areas were effective. Here are three examples where CABS found significant improvements in program outcomes, which may demonstrate how your program can make similar positive changes.

First Steps: Getting People in the Door

Is your outreach meaningful? You may be using multiple strategies to get the word out about your program such as letters, flyers, and emails about your program. Is the message easy to understand? Do materials for participants clearly state how your services can help solve a problem faced by your target population? Do those materials clearly explain how to enroll (including all paperwork prospective participants must bring to the enrollment meeting)?

Example from the field: In an MDRC study to encourage community college students to enroll in summer courses, we tested messaging strategies and financial incentives. In some cases, summer courses could help students graduate on time. MDRC interviewed current students about why they had enrolled in summer courses, and then used these testimonials in the outreach materials for prospective students (Headlam, Anzelone, and Weiss, 2018). The researchers used examples from a peer group to encourage other students to enroll, which is a way to apply the behavioral concept of “social proof” (information about how peers behave in a similar situation). This strategy – coupled with others – increased summer enrollment by 5.5 percentage points over a control group.

You try it! Update a letter or flyer your agency uses to feature a participant’s perspective. Ask a participant how the program helps them reach important goals. Use short quotes or even a longer testimonial, and photos – with permission, of course.

Program Flows: Removing Roadblocks to Program Completion

How does your process flow? Programs with clear, easy-to-follow steps and activities set participants up for success. Extensive requirements such as complex paperwork may discourage participants from enrolling. Similarly, requiring multiple office visits can increase the chances they’ll drop out.

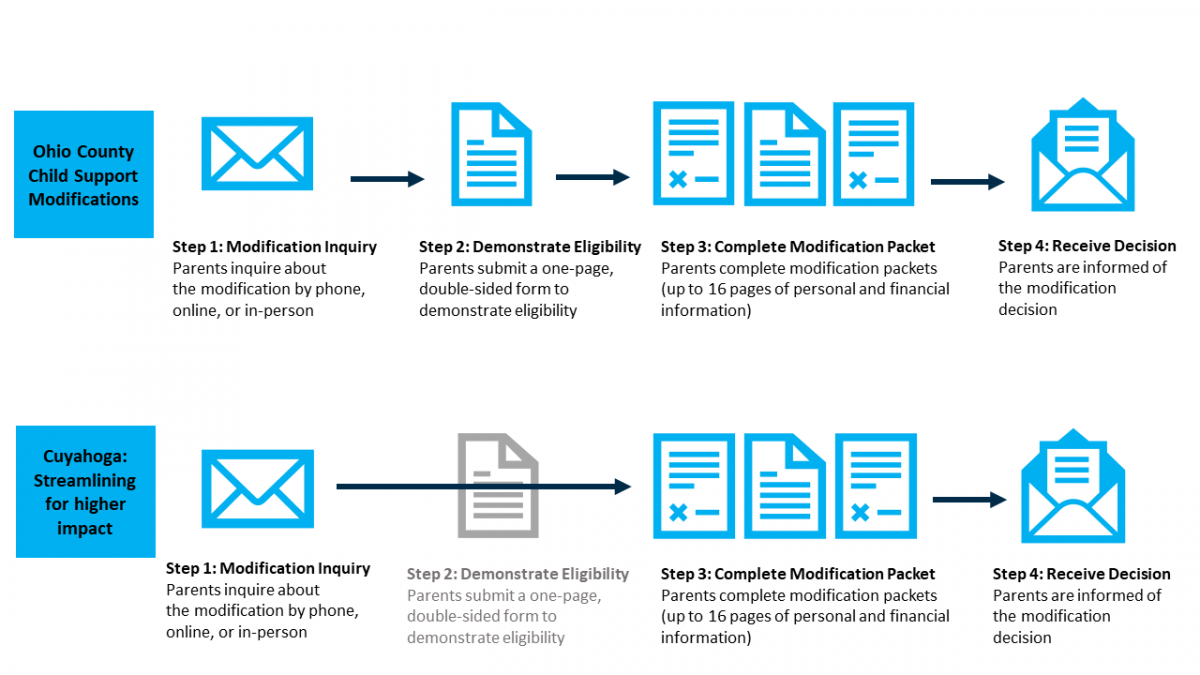

Example from the field: MDRC partnered with a child support program in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, to review the child support order modification process, which ensures that noncustodial parents are expected to pay the appropriate amount. With the goal of streamlining the process, the county government tested a change that made it easier for participants to participate – parents no longer had to demonstrate eligibility for the modification, because staff could check using administrative data. The intervention group completed 38 percent more modification requests compared with the control group (Baird and Miller, 2019). Cuyahoga County made the process simpler and increased the likelihood that participants would complete an application, connecting program design to program goals.

You try it! Review your process, evaluating whether your participants can clearly understand the steps – when activities take place, where they are located, and when they must be completed. Are there unnecessary or redundant steps for either participants or staff? Are there complicated steps that confuse participants? Identify an area you can streamline, making the process easier to complete.

Staff-Client Interactions: Building Positive Connections

Nudges can support participants and staff: Social service staff have a lot to balance while supporting clients toward self-sufficiency outcomes. Is there anything you can do to ease their burden, such as additional planning support by providing them with key information at relevant times?

Example from the field: MDRC worked with childcare providers in Oklahoma to increase the number of subsidies renewed on time. Renewing on time is important for parents because subsidies offset their childcare costs – it’s also important for providers because on-time renewals reduce their administrative burden. In one intervention, the staff role shifted to proactive rather than reactive: childcare provider staff received information about renewal deadlines and prompts to remind clients to renew. This low-cost, staff-focused intervention increased parents’ on-time renewal submissions by 2.4 percentage points above the control group. (Mayer, Cullinan, Calmeyer, and Patterson, 2015) By supporting staff, the designers helped parents, staff, and the agency reach shared goals.

Example from the field: MDRC worked with childcare providers in Oklahoma to increase the number of subsidies renewed on time. Renewing on time is important for parents because subsidies offset their childcare costs – it’s also important for providers because on-time renewals reduce their administrative burden. In one intervention, the staff role shifted to proactive rather than reactive: childcare provider staff received information about renewal deadlines and prompts to remind clients to renew. This low-cost, staff-focused intervention increased parents’ on-time renewal submissions by 2.4 percentage points above the control group. (Mayer, Cullinan, Calmeyer, and Patterson, 2015) By supporting staff, the designers helped parents, staff, and the agency reach shared goals.

You try it! Personalized assistance can go a long way in helping people reach their goals. Talk to staff about ways to help them help clients meet goals. This might improve client outcomes and may also reduce unnecessary burdens on staff and boost morale.

The structure of your program influences your staff and your clients and setting clear program goals can help you design to reach them. The more intentionality you can bring to designing your program, the closer you may come to realizing your goals.